The ML product lifecycle (and how PMs should think at each stage)

Machine learning is changing how we build products — not just what products do.

Traditional software follows a predictable pattern: define the logic, design the flow, ship the feature.

ML products don’t work like that.

They learn.

They evolve.

And if they’re not designed deliberately, they fail quietly.

Most PMs try to apply traditional product practices to systems that behave very differently. ML isn’t deterministic — it’s probabilistic. It requires a different mindset, a different workflow, and a different kind of product leadership.

In one of my recent posts, The AI Product Manager: Redefining How We Build and Learn, I described how the PM role shifts when your product starts learning instead of executing.

This post goes one level deeper.

Today, we’ll walk through the ML Product Lifecycle — the end-to-end process of building ML-powered products — and what PMs should do at each stage to turn predictions into real product value.

Here’s what we’ll cover:

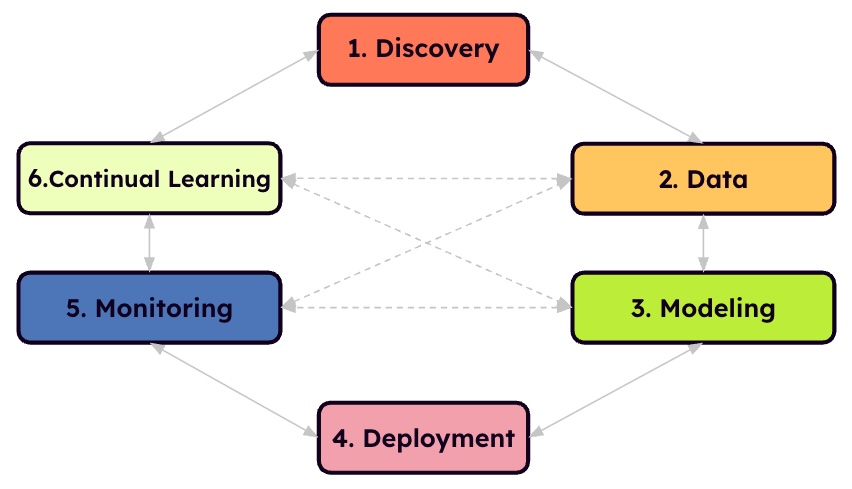

The ML product lifecycle

- Discovery — where value, feasibility, and data meet

- Data — understanding, evaluating, and labeling the raw data

- Modeling — defining success and managing trade-offs

- Deployment — making the model useful in the real world

- Monitoring — catching decay before users feel it

- Continual learning — closing the loop and improving over time

Throughout the lifecycle, one thing stays true:

The ML lifecycle is not a linear process.

Teams don’t march through these steps in perfect order.

You move back and forth between them, revisit earlier decisions, and skip ahead when needed — all in service of learning faster and delivering value sooner.

Now, let’s get into it.

1. Discovery: Start where value, feasibility, and data intersect

Every ML product begins with the same question:

Should we solve this with ML at all?

In The Hidden Costs of Skipping Product Discovery, I wrote about how rushing past problem definition leads to building the wrong things.

With ML products, that risk is even higher.

In classic product discovery, we assess four risks:

- Value risk: Will customers use or buy this?

- Usability risk: Can they figure out how to use it?

- Feasibility risk: Can engineering build it?

- Business viability risk: Does it work for the business model?

ML adds a fifth:

- Data feasibility: Do we have the data — in the quantity, quality, and form — needed to train an ML model that solves the problem?

You can have a valuable customer problem, a clear user need, and strong business alignment — but without the right data, an ML solution is a dead end.

In discovery, your job is to assess — at a high level — whether ML could realistically work:

- Do we capture the type of data this ML task requires?

- Is ML likely better than rules or manual work?

- Are there data signals we expect to exist, even if we haven’t explored them yet?

- Is the scale of the data meaningful enough to learn from?

You don’t need to go deep yet — just far enough to understand whether you have the data to fuel a machine-learning solution. At this stage, you’re only deciding whether ML is even plausible.

A grounded example

“Customers are frustrated by slow response times. Support agents manually triage every request, which doesn’t scale. We need a way to classify and prioritize tickets automatically to reduce delays and improve satisfaction.”

Clear problem.

Clear value.

Clear limitation of rules.

Clear justification for ML.

Clear data collection and understanding — existing data and signals that an ML system can learn from.

That’s what ML-ready discovery looks like.

2. Data: Understand, evaluate, and label the raw material

Discovery gives you an initial signal: Do we even capture the type of data this ML problem needs?

But that’s only surface-level.

The data stage is where you dig deeper and determine whether ML is realistically possible — not in theory, but in practice.

In ML products, data is the product.

Models only learn the patterns the data can teach them — nothing more, nothing less.

The goal of the data stage is to understand the raw material your model will learn from. That means going beyond “do we have data?” and into:

- whether we have enough examples of the outcome we want to predict

- whether the signals are strong enough for a model to learn

- whether the data reflects real user behavior (not just a cleaned-up artifact)

- how noisy, incomplete, or biased the data is

- whether important context is missing (e.g., ticket conversations, ticket types, resolution outcomes)

- whether labels can be applied consistently

A simple truth many teams learn the hard way: If the data can’t teach the model anything meaningful, the rest of the lifecycle doesn’t matter.

Once you’ve confirmed that ML is realistically possible, the PM’s role becomes threefold:

Understand the data

This is where PMs start digging deeper.

In one churn prediction example, two datasets existed:

- Dataset A: perfectly clean, well-structured… and contained zero churn cases.

→ Impossible for the model to learn anything. - Dataset B: messy, inconsistent, full of missing values… but contained real churn signals.

→ Far more valuable.

The lesson:

Look for real-world data with strong signals that help you predict user behavior, because “perfect” data without the right signal is useless, while messy data with meaningful signals is gold.

To guide the team, a PM needs to understand:

- which data point, fields, or attributes matter

- how they map to real behavior

- where gaps or biases exist

- whether the dataset reflects how users actually behave

PMs don’t need to be data scientists — just good storytellers. And real data is always messy. I’ve never seen a perfect dataset, which is why you need to explore it deeply before a model can learn anything meaningful.

Define data requirements

This is product intuition meeting data science.

You might hypothesize:

“Users who submit multiple support tickets and show declining activity may be at higher churn risk.”

That hypothesis translates into:

- ticket counts

- last activity date

- subscription status

- satisfaction scores

- payment history

The PM defines why these matter.

Data teams define how to collect and process them.

Label your data (the human teaching step)

Labeling is one of the most underestimated — and often most expensive — parts of the ML lifecycle.

It’s the moment where humans teach the model what something is — good, bad, risky, fraudulent, toxic, churned, resolved, important.

And this is where reality kicks in:

labeling is not data entry.

It’s human interpretation.

Real-world labeling is messy because people interpret things differently.

In one project, three annotators labeled the exact same dataset — and agreed on only 23% of the cases. Same inputs, three experts, completely different outcomes.

This is why labeling introduces judgment, ambiguity, bias, inconsistency, and endless edge-case debates. The model absorbs all of it.

If humans can’t reliably agree on a label, the model won’t either — because it only learns the patterns we give it.

Labeling can be done by domain experts (like doctors labeling X-rays), by product teams familiar with the data (like support teams labeling tickets), or by trained annotators following your guidelines. There are also automated labeling methods, but that’s beyond the scope of this blog.

The PM’s role is to make those guidelines usable and consistent: define ambiguous cases, align reviewers, surface disagreements early, and ensure labeling quality improves over time.

Because ultimately:

Labeling shapes the worldview of your model — and if the labels are inconsistent, the model will be too.

3. Modeling: Define success and understand trade-offs

Once the data is ready, modeling begins — the stage where data scientists train algorithms to recognize patterns and make predictions.

For example, in a churn use case, the model learns that certain behaviors (like frequent support tickets or declining activity) often precede cancellations. It doesn’t learn why users churn — only that these patterns historically correlate with churn.

That distinction matters.

PMs don’t choose algorithms or tune hyperparameters.

But they do shape the success of modeling.

Define what “good” looks like

This means turning business outcomes into measurable model targets.

For churn prediction, this might be:

“We want to identify at-risk users with at least 80% recall because missing a churned user is more costly than flagging a few false positives.”

In other cases, precision, latency, or fairness may matter more.

The PM owns that decision — not the model code.

Ensure data and labels match the problem

If the data is too clean to reflect reality, or the labels are ambiguous or inconsistent, a model may look great in a notebook but fail the moment it hits production.

Validating this isn’t a solo PM task — it’s a shared responsibility between Product and Data Science. Together, you confirm that the training data truly represents the behaviors the product needs to act on.

Understand what the model will — and won’t — learn

Models learn correlations, not causes. They capture patterns in the data, not business rules.

That’s why PMs, working closely with Data Scientists, need a clear picture of the model’s boundaries:

- What signals does the model rely on?

- Where does it get confused?

- Which predictions are high-confidence vs. shaky?

- Which types of errors are acceptable — and which aren’t?

This understanding shapes the downstream workflow and user experience — what happens when the model is right, wrong, uncertain, or biased.

Make trade-offs explicit

Every modeling decision introduces trade-offs.

PMs shape the decisions; Data Scientists test and validate them.

Some of the common trade-offs include:

- optimizing for recall increases false positives

- aiming for speed increases cost

- maximizing accuracy often reduces explainability

- pushing for fairness may reduce raw performance metrics

The goal is to choose trade-offs that align with user impact, risk tolerance, and business strategy.

Notebook work (what to expect, not what to do)

Modeling usually happens in Jupyter notebooks — tools where data scientists mix code, data, and visualizations in one place.

This is where they:

- test different algorithms

- evaluate features

- tune parameters

- compare performance

PMs don’t need to write code here — but they do need to understand the data science workflow well enough to know how decisions are made.

That context allows them to ask the right questions and interpret the results confidently:

- “What data went into the model?”

- “How are we measuring success?”

- “Where does the model fail?”

- “How confident are we in these predictions?”

- “What actions will this prediction trigger in the product?”

Because at the end of the day: A prediction is only valuable if the team knows what to do with it.

4. Deployment: Where the model becomes a product

A model has zero value until it reaches users.

Deployment is the moment where ML stops being an experiment and becomes part of the real product — whether it’s exposed through an API, embedded in a backend service, or surfaced as a user-facing feature.

This is where PMs step into a critical role. They shape:

- How predictions show up in the product

- Who sees them and why

- What action they trigger

- What latency is acceptable

- What happens when the model fails or is uncertain

Most ML products don’t fail in the modeling stage — they fail here.

Not because the model is wrong, but because the integration doesn’t create real, tangible value for users.

In many cases, before a model moves fully into production, it’s already been tested with a small percentage of users or run quietly in the background to validate that it behaves correctly. You don’t just “push it to prod and hope for the best” — you gradually build confidence that it works in real-world conditions.

Deployment is where the model encounters real-world constraints: UX, infrastructure, cost, reliability, and user expectations.

It’s the bridge between “it works in a notebook” and “it works for customers.”

And it’s often the moment teams discover whether the model was solving the right problem in the first place.

5. Monitoring: ML systems decay — quickly

Traditional software breaks loudly.

ML breaks quietly.

A model won’t alert you when it’s wrong — it will simply start giving poor predictions, and you may not notice until users, support teams, or metrics flag something unusual.

Models drift as behavior, markets, and data pipelines change. Monitoring is how you detect that drift before users feel it.

Teams should track both model performance and product outcomes, including:

- Model health: precision, recall, latency, fairness

- Data drift: are inputs changing?

- Prediction drift: is the model becoming overconfident or inconsistent?

- Business impact: are retention, costs, satisfaction, or efficiency moving in the right direction?

While Data Scientists lead the technical monitoring, PMs often see the earliest signals — through user feedback, support insights, or shifts in key metrics. Sometimes decay shows up in places you don’t expect.

I’ve even seen people on Twitter or Reddit complain that a previously great feature had “stopped working.” When we dug deeper, users had changed their behavior and the model needed fresh data and relabeling.

To keep the system healthy, PMs define:

- which metrics matter most

- what thresholds trigger action

- how quickly the team investigates issues

- how to balance responsiveness vs stability

If a model is live, it must be monitored — no exceptions.

Monitoring doesn’t fix the model. It tells you when it’s time to act.

6. Continual learning: The model is never “finished”

Monitoring tells you something has changed.

Continual learning is how you respond.

This stage is about keeping the model healthy, accurate, fair, and aligned with current user behavior — not the world as it looked when you trained it months ago.

Continual learning includes:

- Collecting new, relevant training data

- Labeling fresh examples (especially where the model struggles)

- Retraining or fine-tuning the model

- Adding new features or signals

- Adjusting thresholds based on new patterns

- Updating the UX around predictions so they stay useful

- Re-evaluating what “good” looks like as the product matures

The loop never ends — and that’s the point.

ML products succeed through iteration, continual learning, not “launch and forget.”

This is why ML product managers must think in learning loops, not linear roadmaps — something I emphasized in The AI Product Manager.

Conclusion: ML products require a different kind of product leadership

The ML Product Lifecycle changes how teams discover, build, test, deploy, and evolve products.

ML products don’t just execute — they learn.

And the PM’s job is to design, guide, and evaluate that learning system end-to-end.

At Chovik, we help teams navigate the full lifecycle — from problem framing and data evaluation to modeling alignment, deployment strategy, and continuous improvement.

If you're building or scaling an AI/ML product and want clarity, direction, or hands-on support, let’s talk.